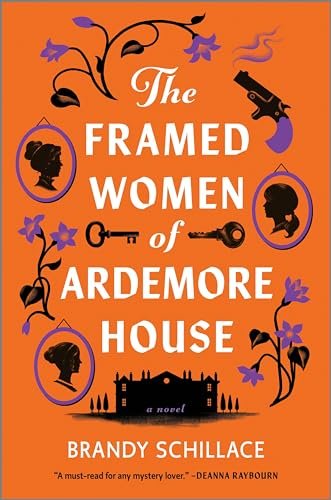

Framed Women of Ardemore House is a gripping, suspenseful, fish-out-of-water crime novel about an American woman with autism who suddenly inherits an eerie, dilapidated British mansion where, shortly after her arrival, a man is murdered.

We had a demanding time putting this book down, but when we finally finished it, we had the opportunity to interview its author Brandy Schillace, is an autistic American herself. We discussed the gripping plot twists and themes of Framed Women , including how more novels like hers feature autistic characters who are convoluted people with fascinating lives, rather than being constrained to Very Special Autism Stories.

Autism Thinking Guide: How would you summarise the plot of The Framed Women of Ardemore House?

Brandy Schillace: Jo Jones has always had a demanding time fitting in. As a neurotypical, hyperlexic book editor and divorced Novel Yorker transplanted to the English countryside, Jo doesn’t know which stands out more: her Americanisms or her autism. After losing her job, her mother, and her marriage all in the span of a year, she couldn’t be happier to take possession of her family’s possibly haunted (and clearly unwanted) North Yorkshire estate. But when the body of the city’s moody gardener turns up on her carpet with three bullets in its back, Jo finds herself in potential danger—and a potential suspect. Meanwhile, a peculiar family portrait disappears from a secret room in the manor house, which has a strange connection to both the body and Jo’s mysterious family history. With the lend a hand of a Welsh antiques dealer, a brooding local detective, and the wife of the Irish innkeeper, Jo sets out on a mission to clear her guilt and find the missing painting, uncovering a host of secrets about the town—and herself—along the way. And she’ll have to do it all before the killer strikes again.

TPGA: Was writing a British crime novel a long-term goal? And how did you decide on the twist of making your main character, Jo Jones, an American?

Schillace: I’ve always loved a good crime novel, and started with Agatha Christie and Conan Doyle. As an American, I also spent a fair amount of time moving to the UK (first as a student, then as a summer intern). It can be really weird—even impossible—to be in a culture that’s *almost* but not quite the same as yours (the same language, for example). Sure, I’ve made mistakes. But I make mistakes; I’m autistic and I can misinterpret situations at the best of times. Oddly enough, when I’m abroad, a lot of people attribute that to me being “American” rather than autistic. (“Are all Americans like that?” is a question I’ve heard). So, in partial answer to your next question, I thought it would be great to introduce an autistic character into the “fish out of water” scenario that most people see NO her neurodiversity, but also her American accent and mannerisms.

TPGA: Do you find it easier to write about an autistic character like Jo in a different country than in her home country, because she would automatically be considered weird and not necessarily neuroatypical?

Schillace: Easier? No, I don’t think so. But it reflected my own experience, and I felt it was a good way to break away from the senior, sorrowful pattern of creating an AUTISM character, rather than introducing a CHARACTER who happens to be autistic.

TPGA: Do you see yourself as part of recent factual fiction where autistic women like Jo can be openly neuroatypical, fascinating, cheerful, and live life on their own terms, and their autism shouldn’t be the Very Specific Focus of the plot? I’m thinking of Olivia in Sinking into the depthsRose with Camp Damascuseven Molly in the series “The Handmaiden” – although this character there is no formal diagnosis.

Schillace: Believe it or not, I didn’t come across any of these other stories or authors until I wrote the book. In fact, I’d never seen a single book (when I started) that actually portrayed an autistic character in a way that helped me “see” myself. My goal was for her to be neurodivergent in the way that you could have a character with any other trait—still, shy, or introverted, for example. It’s just something about her. I’m all autistic, but I still don’t think that’s the most fascinating thing about me.

TPGA: Following on from the previous question, has anyone involved with TFWOAH encouraged you to engage more with autism content?

Schillace: My agent was the first to suggest that I have the character admit to being autistic (instead of being less obvious). At the time, I was less “open” about my own autism. So I decided to go public with my own diagnosis before I reframed the narrative. I wrote a piece called Coming Out autistic for Scientific American, where I struggle with stigma and fear of being outed (as a kid who grew up in the 70s/80s). Then I rewrote the book, allowing Jo to come out and be autistic. Then my editor asked me to add even more of Jo’s weirdness to the novel, which wasn’t a request for stereotypes—it was just a request for “let’s show her more of who she is.” I’m pretty sure that’s the first time in my entire life that I’ve been encouraged to be “more” autistic about anything.

TPGA: My favorite moment in the book is when Joe tells her internalized neurotypical skeptic voice to “fuck off” from doing info dumps. Is that something you do (or have learned to do) or is it an aspiration? I imagine it’s a helpful habit for self-preservation.

Schillace: Oh, I have whole conversations with myself all the time. And I definitely armed myself with weapons against the pressures of NT. It took me years to accept myself and demand some accommodation from others, some space. I wanted Jo to have that.

TPGA: Jo has integrity and expects it from others, which was particularly damaging to her during her divorce from her cheating, scheming husband. Have you witnessed autistic friends or loved ones being deceived or manipulated in similar ways?

Schillace: Oh my. Yes. That’s how it is — as an autistic person, I always try to read and translate for those around me. I want to anticipate their needs, know what they’re trying to say and expect, so I can respond in kind. That means I’ve already done a lot of the work before the conversation even begins. The problem is that NT doesn’t do that for you. At least not often. They say they want to meet you halfway, but they mean “ten steps,” and I’ve already walked a thousand to be here. We expect people who are different (disabled people in general, but many other minority groups) to do all the demanding work. At some point, I realized I was a mule for other people’s expectations.

TPGA: I really appreciated the Welsh archaic dealer Gwilym and his admiration for Jo’s editorial and archival skills – especially the fact that he thinks she’s talented and skilled, rather than weird or too direct. And of course, it turns out he’s also neuroatypical, although in his case (spoiler) it’s ADHD. Have you heard of the idea neurodiverse “cousins” before you decide about the dynamics of your interactions?

Schillace: I’ve never heard of that! Fascinating. I just knew that my journal was helped by other neuroadivergent people, those who were better at expressing their needs, had better support. They helped me come to terms with my autism and see the value in myself. I wanted Gwilym to be a little further along that path of self-advocacy and to lend a hand Jo along the way.

TPGA: TFWOAM also has open feminist threads on the complexities of sex work and historical views on out-of-wedlock birth, two topics that aren’t always treated fairly by mainstream writers. Can you talk about what prompted you to include these threads?

Schillace: I’m glad you asked! I work in the social justice field in general. I’m pro-LGBTQIA+. I support women, I believe trans women are women, and I believe we all have the right to our bodies. There are those who limit feminism to what I consider a pretty narrow and patriarchal box — one that denies women their sexuality, their fluidity, their rights to themselves, their decisions. Sex workers are often caught up in this and treated as victims or infantilized. Of course, we all need to protect women from exploitation 100% (and there are some men in this story who are trying to do that), but when a woman (or man) chooses sex work — of their own free will, not out of coercion — we need to respect that choice and not judge.